08 Jun Tom Paine’s Bones

Poor old Tom Paine! there he lies:

Nobody laughs and nobody cries

Where he’s gone or how he fares

Nobody knows and nobody cares.

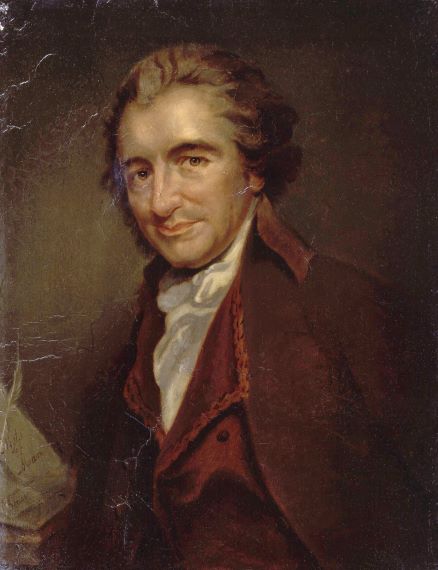

Two hundred and eleven years after his lonely death on June 8, 1809, belittled and forgotten by the country he helped create, why should we still care about Thomas Paine?

We should care now more than ever, because as Paine biographer Craig Nelson explains, “Almost everything about America and Americans that is globally admired today is found in his work; almost every issue he raised is still an issue in our times; almost every argument in which he engaged . . . is still being argued two hundred years later.” And, as the astonishing events of the past few weeks have shown, Americans and the rest of the world still believe passionately in the ideals that fueled our Revolution, and that America can still become the country Thomas Paine envisioned when he wrote the document that would change history.

Human dignity, civil rights, slavery, the role and power of government, women’s rights, political and economic equality, justice, institutionalized religion – all topics of Paine’s confrontational and uncompromising body of work. Paine used the power of the written word as a weapon against repressive social structures and the arbitrary, self-serving abuse of power by individuals and institutions alike. He rose from a hardscrabble early life in working-class England to become a powerful political writer and founding father to both the United States and the French republic. He survived the revolutions of both countries.

Paine’s extraordinary life is well represented in several great biographies (see Resources), but for me, looking at it through a musical lens is irresistible. There are a lot of great versions of the song “Tom Paine’s Bones,” by Graham Moore, but I am partial to the one by these bad-ass ladies from Melbourne.

Stray Hens – “Tom Paine’s Bones”

TOM PAINE’S BONES (Graham Moore)

As I dreamed out last evening by a river of discontent

I bumped right into old Tom Paine

As a-running down the road he went

He said I can’t stop right now my son King Georgy’s after me

He’ll have a rope around my throat and hang me on the liberty tree

And I will dance to Tom Paine’s bones

I will dance to Tom Paine’s bones

I’ll dance in the oldest boots I own

To the rhythm of Tom Paine’s bones (rpt)

He said I just wrote about freedom and justice for everyone

Ever since the very first word I spoke

I’ve been looking down the barrel of a gun

Well they say I preached revolution but let me say in my defense

All I did wherever I went was to talk a lot of Common Sense

Well old Tom Paine he ran so fast he left me standing still

And there I was a piece of paper in my hand

Standing at the top of the hill

And it read “this is the Age of Reason these are the Rights of Man

Kick off religion & monarchy” it was written there in Tom Paine’s plan

“King Georgy’s after me. He’ll have a rope around my throat and hang me on the liberty tree . . . . All I did wherever I went was to talk a lot of Common Sense” – King George III would absolutely have had Paine hung from the nearest “Liberty Tree” – a symbol of resistance throughout the American colonies before and during the Revolution. Up to early 1776, despite the increasing hostilities between England and her 13 colonies, most people, including the newly appointed commander of the Continental Army, George Washington, hoped for a peaceful reconciliation with England, rather than a fight for complete independence. But on January 10, 1776, an anonymous pamphlet called Common Sense was published in Philadelphia and ignited a firestorm of public debate. Unlike most political pamphlets at the time, which used verbose language and philosophical references, the 46-pages of Common Sense were written in a direct, unadorned style, meant to for a mass audience. That audience, far from the unified, defiant coalition that is sometimes mythologized in U.S. history lessons, was a group of colonies which were politically, economically, culturally fragmented and largely undecided about what the ultimate objective of their grievances against the Crown should be. Common Sense attacked the very idea of monarchy, the illogical emotional and intellectual bonds between the colonists and England, and articulated a straight-forward argument for complete freedom from British rule.

By uniting the colonies behind the idea of independence, Paine animated a nation and changed the entire scale of the conflict. Soon after reading Common Sense, George Washington recognized the global significance of the war, and that in the Americans’ struggle for self-determination rested “the fate of unborn Millions.” Although the author of Common Sense was initially only identified as “an Englishman,” Paine soon became a tenacious advocate for the war and continued using his literary skills to promote the Revolution.

“And it read “this is the Age of Reason these are the Rights of Man . . . Kick off religion & monarchy” it was written there in Tom Paine’s plan.” – Paine returned to England in 1787, as France rumbled with ominous uncertainty. In 1789, he visited a volatile Paris at the invitation of the Marquis de Lafayette, and immediately took up the cause of the Revolution. “A share in two revolutions is living with some purpose,” Paine wrote to George Washington. The Rights of Man, published in 1791, not only defended the French Revolution, but eviscerated the systems of English monarchy and aristocracy. Attacking the inequity between workers and the idle rich, Paine argued that such a construct created poverty, “One extreme produces the other: to make one rich, many must be made poor; neither can the system be supported by other means.” Paine proposed the introduction of luxury and inheritance taxes to fund a social system which would include public education for all children, old age pensions, income for families with newborn children and welfare payments to the poor.

Naturally these ideas did not resonate well with the British government, who charged Paine with sedition in 1792. Warned by a friend that he would soon be arrested, and taunted by mobs chanting that he should be tarred and feathered, Paine fled from Dover to France. He was initially welcomed and awarded honorary French citizenship. But as the French Revolution grew more chaotic and violent, Paine soon became a victim of its mercurial leadership and was arrested in December 1793 for his support of exile, rather than execution, for the deposed King.

Paine was one of eighty thousand French citizens imprisoned by June of the following year; in six weeks during that summer, the French government executed 1,376 people. Imprisoned just short of one year, Paine barely escaped execution, thanks to the intervention of James Monroe, the American ambassador at the time. While in prison, despite failing health and the ever-present threat of the guillotine, Paine continued writing his third controversial work, The Age of Reason. In this book, Paine explained his personal religious belief in a creator-God, but argued against the validity of the Bible as anything but a work of literature, and condemned the political power and corruption of institutionalized religion. The Age of Reason earned Paine the wrath and hostility of many readers in both Britain and America. By the time Paine returned to America in 1802, his contributions to his adopted country were largely forgotten. Paine died on June 8, 1809 in New York.

“Tom Paine’s Bones” – The restless trajectory of Tom Paine’s life did not end with his death and burial. Worried about backlash because of Paine’s reputation as an atheist, the Quaker church of New Rochelle denied his request to be buried in their cemetery. Paine was buried on his farm with the simple headstone, ‘Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense.’ In 1819, the English journalist William Cobbett, a once ardent critic of Paine who later became a zealous fan, decided that Paine deserved more than an obscure grave in the country that had failed to properly recognize his greatness. Cobbett traveled to New York and in the dead of night, dug up Paine’s bones and sailed with them back to England. Upon his arrival in Liverpool, Cobbett announced to the customs agents, “There, gentlemen, are the mortal remains, of the immortal Thomas Paine.” The bones were still among Cobbett’s effects when he died over fifteen years later.

Resources:

Thomas Paine, by Craig Nelson

46 Pages, by Scott Liell

Tom Paine, by John Keane

Feature image – “The Political Champion turned Resurrection Man!”, Cruikshank, Isaac Robert (1789-1856)