17 Mar March 17, 1776 – The British Evacuate Boston

In the early months of 1776, George Washington, whose Continental forces had surrounded the British in occupied Boston for almost 11 months, wanted to make a ‘bold attempt’ to force the British out. With few good options, limited arms and ammunition, and an untrained, untested army under his command, Washington ultimately decided to try to capture Dorchester Heights, which overlooked Boston Harbor from the south. Securing the elevated area would give the Americans the ability to attack the British from above and prevent ships from bringing in new supplies by sea. The British would either have to fight for the heights or evacuate the city. The one thing Washington did have in his favor was the arrival in late January of Henry Knox and his ‘noble train of artillery’ – 60 tons of cannons and other weapons retrieved from Fort Ticonderoga and brought back on an arduous 300 mile journey through deep winter snow.

Once Washington made his decision, things moved quickly. First, he created a diversion by placing some artillery in Cambridge and Roxbury. During the nights of March 2-4, the city was bombarded. On March 4, the cannons continued their distracting fire, while two thousand men built defenses of felled trees, hay and ‘gabions’ (wicker baskets stuffed with dirt). All night long, oxen hauled cannons and wagons full of armaments up the steep, icy hills. The pounding of the cannons drowned out the sounds of the huge operation, and a fortunate low-lying fog enveloped the city, hiding the movements from the enemy’s view. When the entrenchments were completed, three thousand fresh troops moved into place. Map – Boston 1776

The morning of March 5 greeted the British with the sight of American infantry and artillery looming over Boston harbor, protected by massive defensive emplacements. An astonished General Howe commented that “the rebels have done more in one night than my whole army could do in months.” Howe was soon prepared to attack with two thousand men, but a powerful storm forced him to postpone, and reconsider his position. In their now almost indefensible position, any attempt by the British to take the heights would mean a bloody, risky battle, which Howe had little stomach for after the previous summer’s costly victory at Bunker Hill. On March 7, Howe made Washington an offer – allow the British to leave the city peacefully, and he would not put a torch to Boston. Ten days after Washington agreed, the last British ship sailed away, thus ending an eight-year occupation of Boston. Knowing that smallpox had been present in the civilian population since the early days of the siege, Washington ordered that only soldiers who had already survived the disease make up the first regiment to enter the newly liberated city.

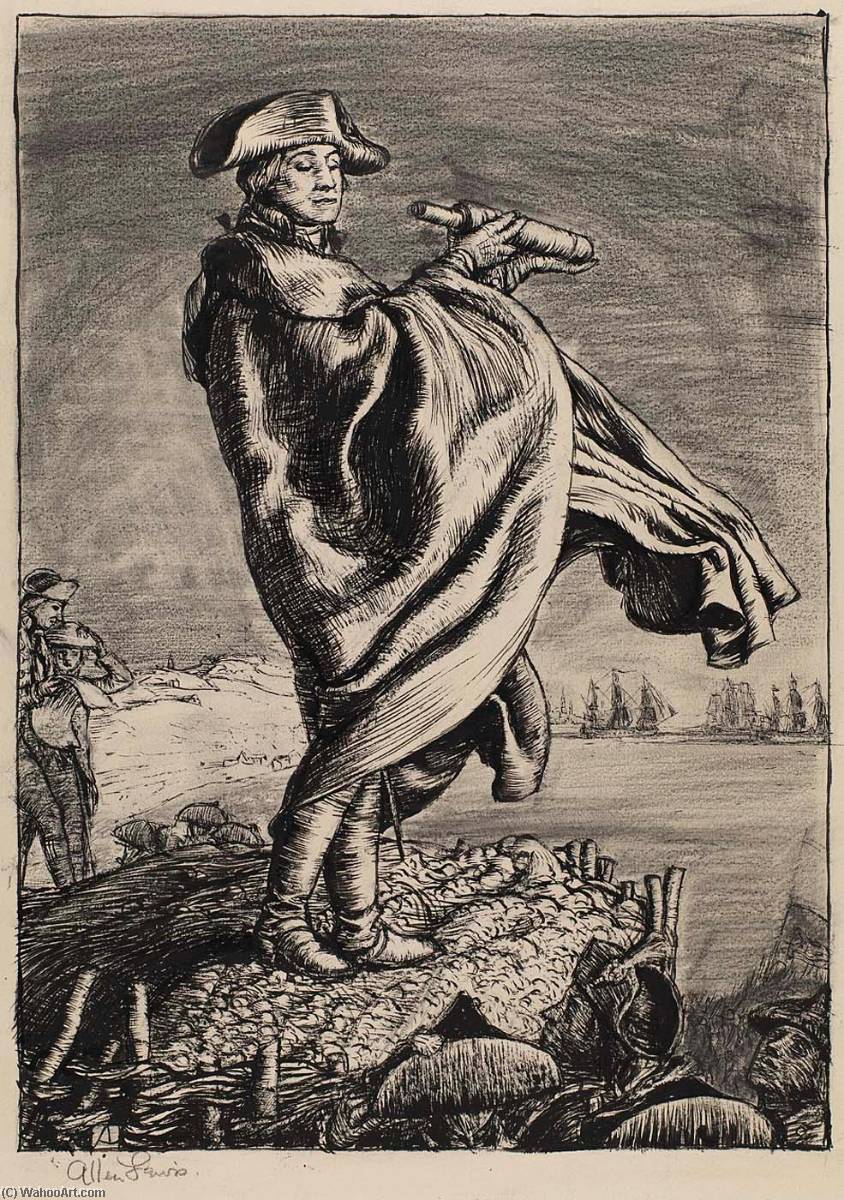

Feature image – “The British Evacuate Boston” – Allen Lewis, Smithsonian Library.