10 Jan The Pen of Paine

“Without the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.” John Adams

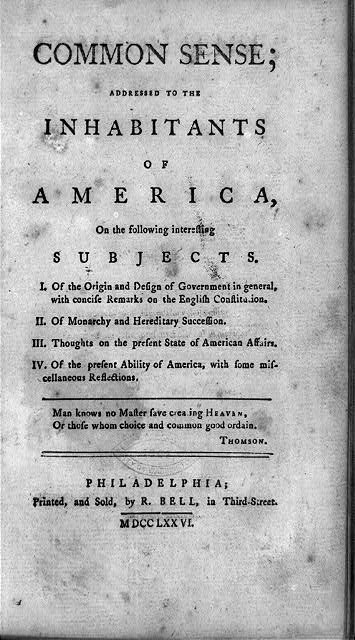

January 10, 1776. A political pamphlet, forty-six pages long and written by the anonymous author “an Englishman”, hit the streets of Philadelphia. In a few months,Thomas Paine and Common Sense, would change the future of America, and the world.

In 1774, Thomas Paine left his native England at the urging of his friend and mentor, Ben Franklin, and sailed to America. The rumblings of rebellion against England were growing louder and Paine, with the zeal of a true Enlightenment thinker, took up the cause immediately. Over the next year, events accelerated – fighting at Lexington and Concord; the creation of the Continental Army; the Battle of Bunker Hill and siege of Boston, and King George’s adamant rejection of the Olive Branch Petition. During this time, Paine wrote and edited the Pennsylvania Magazine, covering a wide variety of topics – medicine, science, history, poetry, women’s rights, the abolition of slavery. In April 1775, following the first shots fired between militia and British troops, Paine wrote a series of articles instructing private citizens how to make salt-peter, a primary component of gunpowder. In response to escalating tensions with his American subjects, George III had banned the import of firearms and gunpowder from Europe, and had been confiscating them in a bid to disarm the rebellion.

By late 1775, when Paine began writing Common Sense, many colonists were still unsure of their cause and the next steps. The issue was debated constantly and passionately, but the arguments about how to proceed were unfocused. The colonists self-identification as British subjects was a psychological anchor to breaking the bond with the mother country completely. Paine set out to convince his newly adopted countrymen that the noble, just and only solution was to fight for complete independence, and create a democratic republic as a testament to the world on the inherent equality of human beings.

Paine’s arguments were radical, but his direct, plain writing style appealed to the audience he was targeting – the common people. Political pamphlets were typically full of philosophical observations and Latin terms. Common Sense had the feel and language of a sermon, embedded with biblical references that every reader could relate to. The pamphlet began with an introduction, followed by four chapters.

“The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.”

In the introduction, Paine acknowledges the audacity of his proposal, but also the inevitable choice that America must make as the manifestation of Enlightenment ideals of freedom, human progress and self-governance.

“Here then is the origin and rise of government; namely, a mode rendered necessary by the inability of moral virtue to govern the world.”

Chapter 1 of the pamphlet takes aim at the idea of government in general. Paine recognizes that as society grows larger (as the collection of colonies surely would), the need for some government is inevitable, and that a growing society must rely on a limited number of people to make decisions that affect everyone. Therefore, these decisions should reflect the desires of the people as a whole, not an arbitrarily appointed leader.

“In England, a king hath little more to do than make war and give away places; which in plain terms is to impoverish the nation and set it together by the ears. A pretty business indeed for a man to be allowed eight hundred thousand sterling a year for, and worshipped in the bargain!”

Chapter 2 takes aim at the concept of monarchy and the divine right of kings. Full of biblical references, this section refutes the absurdity of complete power over a country resting in the hands of one family, and the tradition of inherited rule. Kings, Paine shrewdly points out, do not suffer the consequences of ill-conceived decisions, whereas their helpless subjects bear the brunt.

“The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth.”

Chapter 3 clarifies the timing and justification for a war of independence, and the practical steps towards creating a political system of representative power among the colonies. In this section, Paine also addresses several of the most popular arguments against a full severance from England. To the assertion that the colonies had been protected and flourished under English rule, Paine countered with the observation that England merely protected America from the enemies of England. An independent United States of America, Paine explains, would be free of wars that suited England’s purposes and free to trade on its own as an equal with other countries. Perhaps the most powerful refutation in this chapter is against the familial connection with British ancestry that most colonists shared. Immigrants from all over Europe, not just Britain, came to America, usually to escape oppression in their home countries, which made the common bond among them a search for freedom, rather than one cultural foundation.

“In almost every article of defence, we abound.”

Chapter 4 is the nuts and bolts of war – the costs of building a fleet of ships; raising an army; the geographical advantages America possessed – a huge coastline, abundant natural resources, especially naval supplies like timber, ore, tar and hemp. Paine notes that America need not feel compelled to compete with the formidable size of England’s navy because the colonies need only defend themselves, while England’s ships were needed all over the world in defense of her extensive dominions.

The first printing of Common Sense sold out in two weeks and over 150,000 copies were sold throughout America and Europe, by the end of the year up to 500,00 copies were in circulation. It is estimated that one fifth of Americans read the pamphlet or heard it read aloud in public. General Washington ordered it read to his troops. By spring of 1776, one colonial assembly after another ratified instructions allowing their delegates to cast their vote for independence. The ideas put forth by Paine changed not only the political direction of the revolution, but the military objective and strategy as well. After reading Common Sense, George Washington recognized that the outcome of the war had universal implications, and the long-term goal of keeping his Army intact, rather than forcing all-or-nothing battles, was the key to wearing England down to a point of surrender.

Paine’s anonymity as the author of the fiery pamphlet did not last long. He went on to write many more pamphlets in support of the war, including the blood-stirring American Crisis – with the immortal words “these are the times that try mens’ souls.” Although Common Sense was arguably America’s first best-seller, Paine never earned a penny from its prodigious sales. He donated all the proceeds of his war-time writings to purchasing food and clothing for the American soldiers.

The momentum towards independence was well under way before Thomas Paine penned the words of Common Sense, but there can be no doubt that his simple prose and formidable persuasion turned the rumblings into a roar that was heard all over the world.

Sources:

Thomas Paine and the Clarion Call for American Independence, 2019. Harlow Giles Unger.

46 Pages – Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence, 2003. Scott Liell.

Thomas Paine – Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. 2006. Craig Nelson.